LOVE TO CRASH

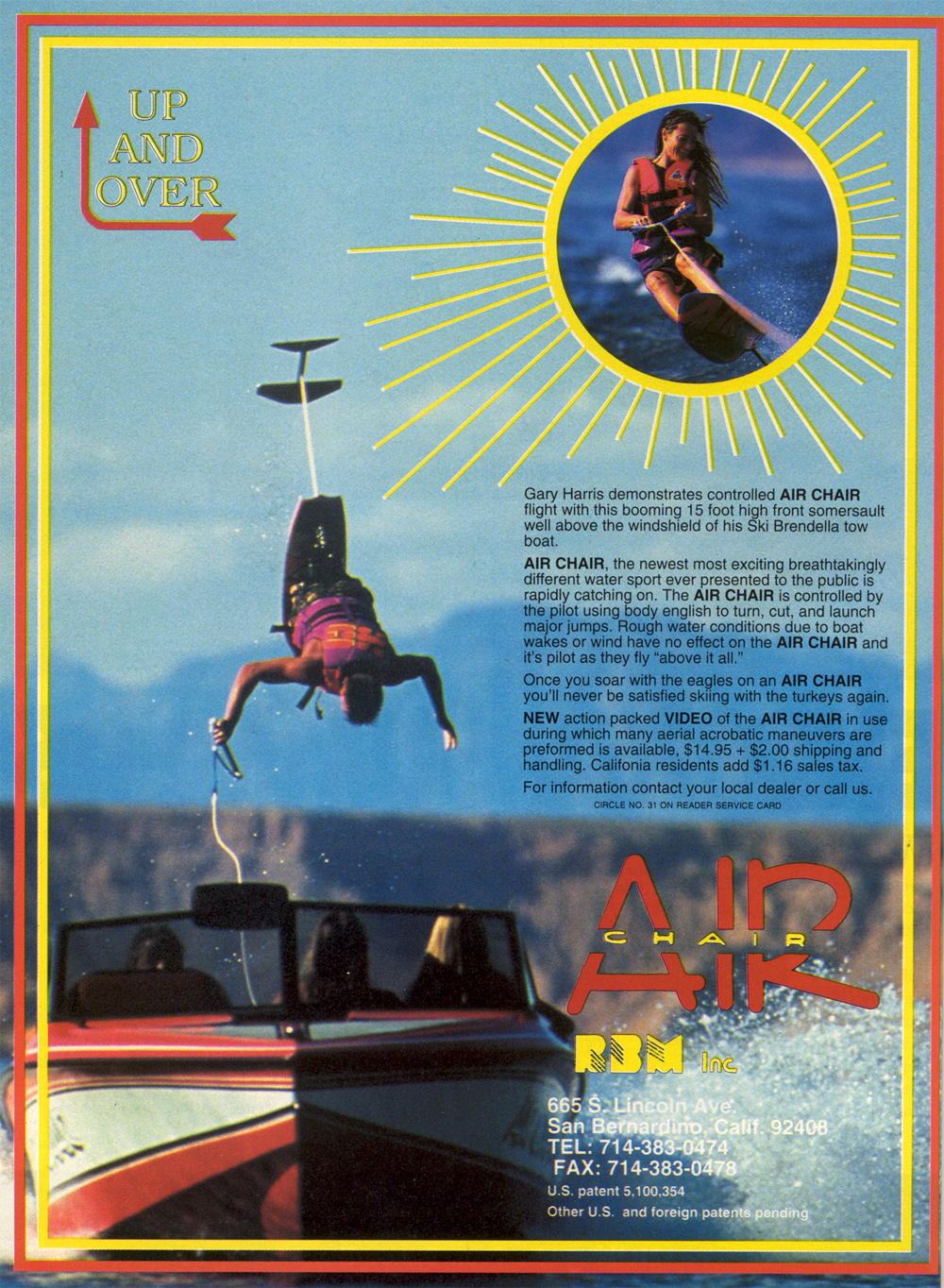

Over the next few years I was in the midst of hard-core riding. Bob Dunham and I worked on compiling a list of the early hydrofoil tricks that documented who was the first to do a particular move and on what date. I reviewed the list that covered the first seven years of sit down foiling from 1989 to 1996. More than 90% of the original tricks list came from uncle Mike, Ron Stack, and myself. The notable exception was Gary Harris who was first person to land a front flip. Harris drew on his experience as freestyle jumper to show us the way to one of the prettiest and most demanding moves in foiling. Others pioneers on the list included Paul Helbauch, the first one to land an invert without riding it out, Bob Woolley for his jumps, Mike Mack for his variations of skidders and jumps, and Dean Lavelle.

Gary Harris was the first to land front flips. (WaterSki Magazine, 1992)

Mike Murphy is most known for being the first to ride away from an invert, but he was also the first to lmake hand-to-hand helicopters. He became a skidding machine after seeing me do the move, and took hour-long rides for weeks doing nothing but Skidders. He eventually came up with the Skidder wake cross, wake jump to Skidder, and the Skid Roll, which was an air back roll that landed in a Skidder. The Ski Roll was the first move in foiling that combined to different elements into one trick. Another original move he called the “Submarine” was an all-time crowd favorite. He got the idea from his friend and world champion Larry Rippenkroeger, the invented the move on a Jet Ski. Back in the day Larry wowed crowds with a move called the “Submarine”. He jumped off the water and landed nose down to dive his Jet Ski completely underwater.

Mike’s signal for the Sub on the hydrofoil was to put his wrist on the top of his head and cup his palm forward to imply the periscope of a submarine. That was our sign to slow the boat down to about seven mph. At that slow speed there was very little lift for a foil directly behind the boat, so Mike cut hard across both wakes to generate enough speed to throw a back roll. He landed wide in the flats, purposely under rotating so the nose of his board would knife into the water. Then he completely disappeared for about two or three seconds. It was just a circle of bubbles with a tight line disappearing in the middle. You could feel the crowd hold their collective breath and then let it out when Mike broke the surface and rode away to their cheers.

Mike Murphy performs submarine at 1998 Flight Worlds

Ron Stack used crossover sports as his inspiration for new moves, especially wakeboarding. He grabbed his board and jumped, just like a monkey on a springboard. He came up with virtually all of the original grab and tweak variations including the nose and tail grabs, Method Air, and Cross Rocket Stiffy.

Ron Stack used his wakeboarding background to lead the way with grabs. (Klarich, 1995)

I was inspired by Ron to grab, but didn’t have his flexibilty…so I went for the closer tower grab on a frontside roll. (Bender, 1995)

One of my toughest tricks, and one that will probably never become mainstream, was the 180 tick tock. I was inspired by one of my hot dogging moves to try it on the foil. I cut wide into the flats, did a 180 to land backwards, then somehow tried to turn the foil back to the normal riding position. After numerous attempts I found the best technique was to try and land backwards in something of a reverse skidder position. The foil would bounce on the water, and I was able to immediately force it back around. All in all I landed 2 out of 100. Fortunately grandma Murphy captured one of them with her VHS camera, and I spent hours try to figure out what in the heck I was doing. I eventually gave up on the move after catching the foil in the backwards position and falling backwards with an extreme whiplash and high-speed smack of my head on the water. That move was just too hard to ever get consistent.

180 Tick Tock on Air Chair

Another one of my moves was to become the basis for a myriad of tricks, and another completely new way to ride. I looked to kneeboarding once again for inspiration, and this time is was the front roll combo. That was another one of the advanced kneeboard tricks it took to stay competitive in the late 1980s, and I had them down.

The only problem in transferring the move to a hydrofoil was the landing. In a regular front roll the foil landed tip up. That went against every rule of the tip down swoop style that was standard for foiling combo at the time. So I set out to break the rules, or at least rewrite them. My thoughts were to work on a basic tip up style combo, and break it down into each distinct part before trying the actual trick.

My wife and I were at our favorite place on the River when I set out to learn the move, hanging out with Mike and Vicki Mack, and uncle Mike. I began with a wake-to-wake jump into an immediate combo jump on the other side of the wake. The landing was tip up, and it was the first combo to use the “sink” style. I performed the jump-to-jump combo with the same set up and positioning that I would be using for the front roll combo so that the angles and timing would be similar. Only Mack knew what I was really working on, so when I told uncle Mike about my new combo trick he was unimpressed. He thought it was just more cheese. In subsequent rides I came up with two more new tricks: the wake jump to frontside roll combo, and wake frontside roll to jump combo. I worked each element of the trick separately, and had already inadvertently come up with three new moves in my preparations. It followed my typical step-by-step learning method. It felt a lot safer than just going for it out of the gate.

At the end of the second day I felt confident enough to throw the actual trick, the frontside roll combo, and made several on my first set. I called it the “Double Barrel.” It wasn’t long before it became a consistent move in my arsenal, and uncle Mike finally took notice. That same week he modified my wake-to-wake combo jumps into a series of combo jumps in the trough of the wake. We called them “Kangaroos,” and they kind of felt like being on a pogo stick! It wasn’t long before our combo variations went crazy with jump-jump-back roll-jump, skidder-roll-jump, and whatever else we could imagine.

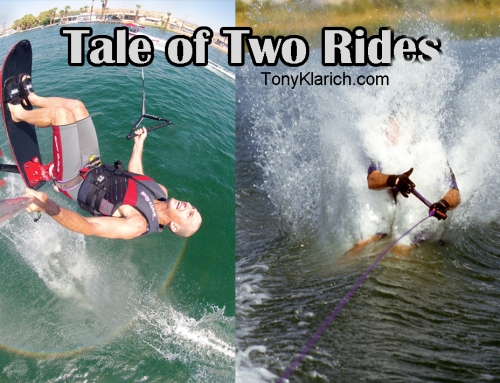

Working on developing new moves was a constant part of my training. A typical foiling ride went something like this. I started out with three or four wide jumps on each side. I took a hard cut all the way across the both wakes and into the flats before launching a nice big controlled jump. Then I did a few big wake jumps on both sides just to stay in touch with that often overlooked skill. Next, I got to the inverts with a couple a gainers on each side in the flats. I concentrated on a good approach, control in the air, and a smooth landing. A well-done gainer is a beautiful thing. The phrase magic carpet ride has often been used to describe foiling, and this trick, more than any other, fits the description for me. It took very little effort to launch an free floating gainer, soar 50 or 60 feet and touch down with a landing like butter.

I followed my gainers with a series of all eight roll variations: all four backside rolls including wake and air from both sides, then all four frontside rolls. Finally I did a few wake front flips and air front flips. I followed those up with helicopters, combos, skidder variations, and whatever else was relatively new. After going through all the “basics”, those tricks which I made almost every time, my next step was to work on my brand new tricks. I always worked on at least three new moves, and always did them in order from easiest to hardest. The first new trick was usually something that I was making, but not entirely consistent on. If I made three in a row, it was time to move on. For the last two new tricks I almost always worked in sets of five. I got this from my show skiing days when the pay for performing a new trick was based on consistently making the move four out of five times in practice and in the show. Using sets of five was also a great way to keep track of my progress, put forth maximum effort on each try, and keep from overtraining. When I knew each trick got only five tries, it allowed me to keep up the intensity for each attempt. By knowing what I made last time out, I also had something tangible to shoot for. As soon as I could consistently make four out of five it was time to add another new trick into the rotation. I used this technique for years to learn new moves, and it served me well. In my heyday I usually skied at least 15 days a month throughout the year. Each day on the water consisted of five to ten sets on all my different ski rides. When it came time to get ready for a specific event. I usually rode six days a week, taking two or three sets a day on whatever it was I was training for.

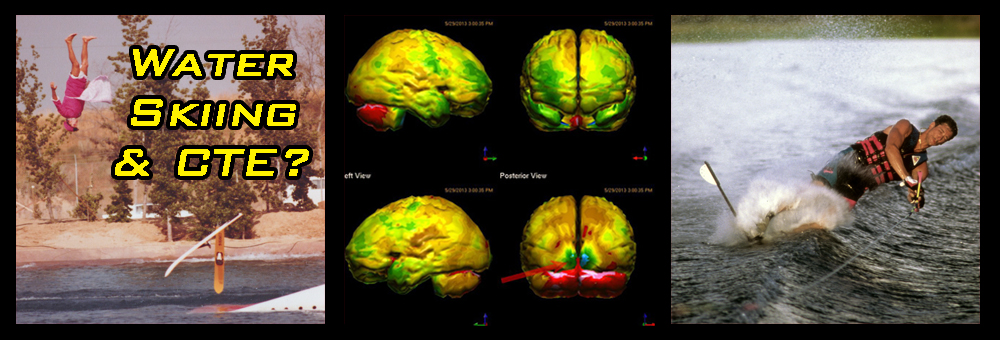

There were countless crashes, but I’ll try to come up with a reasonable estimate. I conservatively rode 150 days a year for well over 20 years. Each day was at least six rides, and each ride had at least 10 falls. So 20 (years) x 150 (days) x 6 (sets) x 10 (falls) = at least 180,000 crashes as a pro skier. I’ll add another 20,000 falls for ages 5-18 and 39-50 (25 years). Just thinking about more than 200,000 crashes seems impossible, but the numbers don’t lie. Grandma Murphy drummed this phrase into my head: “If you don’t fall, you don’t learn anything.” I took her words of wisdom to heart and did plenty of “learning.”

The “Mudhen”: on my way to 200,000+ crashes! (Doyle, 1993)

A key part of my crash protection on the Air Chair was my helmet, but my first choice, a football helmet, was too heavy. To lighten things up I tried a skateboard helmet for a couple of months. The fit and feel was much better, but the foam padding was not made to get wet. It took on water like a sponge, and quickly disintegrated with use ( I am wearing this helmet in the 180 Tick Tock video above). My third helmet was the charm, and it came from Mike Mack. He saw me experimenting with the old brain bucket, and thought it was a good idea too. He had his eye on learning a flip on the Chair, and also wanted to wear something for head protection. As an avid surfer who read the surfing trade magazines, Mack saw some of the big wave riders at Pipeline using Gath helmets. He ordered a couple for his ski shop. For me it was love at first try. The Gath was lightweight and felt good. It did not retain water. I called up Murray’s, the US distributor for the Australian made product, and they sponsored me with three helmets. Mack started selling them at his shop, we wore them proudly, and quite a few riders started wearing Gath helmets too.

Mack’s surf connection brought the Gath helmet to hydrofoiling. (Klarich, 1996)

Mike Murphy was still anti-helmet, but I loved the feeling of confidence that came with my Gath. Another bonus of wearing a helmet came during cold water skiing. In previous years I wore a neoprene beenie, but I soon discovered the helmet was better by a long shot. It had superior fit and the strap was comfortable. For super warmth I added a one-millimeter neoprene hoodie by Body Glove underneath the helmet.

How to Stay Warm While Skiing

I was always thankful to be wearing a helmet during a big crash. Often the worst falls were completely unexpected, such as running into a fish. If the fish was big enough we found ourselves unexpectedly in the water next to a stunned or dismembered victim. It was kind of like running at full speed and getting tripped. But fish weren’t the only submerged objects to be concerned about. One of my hardest crashes came when I was cutting out hard for a gainer in the flats. I hit an underwater buoy near a slalom course and went from 40 mph to smackdown in an instant. There was no warning; just a white flash, a brief blackout, and gasping for breath in the water. Another time at the River my foil hit the rocky bottom in about a foot of water. The area was not known for being shallow, but the water was low because of irregular water flow from the Parker Dam upriver.

My stubbornness to ride with a helmet was always a sticking point for uncle Mike and Air Chair. Even though I was the top rider at Air Chair for several years, they never once used a picture of me in a print ad, poster, or brochure. It probably had something to do with the helmet, but more likely had to do with my photo incentive contract with Air Chair. Bob Woolley always paid me the specified amount for photo appearances, and I got the feeling he didn’t want to cough up a few hundred dollars to use me in their ads.

While I never got my ad, Mike did manage to get his own full-page spread dressed as a nun, complete with a coronet. It was pure Murphy humor and an all-time classic.

Righteous brother! Mike gets to design an ad, 1986.

>Adventures in Water Skiing: SERIES LINKS

RELATED CONTENT

1998 Flight Worlds Crashes

Blog Post:

Images (used with permission)

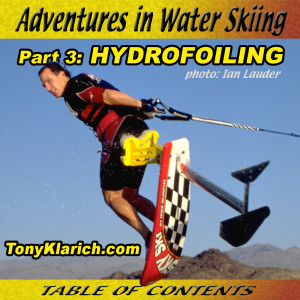

“Adventures in Water Skiing: Part 3, Hydrofoiling – Cover,” photo: Ian Lauder, 1999.

“Air Chair Ad w Gary Harris,” WaterSki Magazine, June, 1992, 34.

“Ron Stack – Tail Grab, photo Tony Klarich, 1995.

“Tony Klarich – Tower Grab Front Roll,” photo Kirk Bender, 1995.

“Tony Klarich – Mudhen,” photo Rick Doyle, 1995.

“Mike Mack – Skidder w Gath Helmet,” photo Tony Klarich, 1996.

“Nun Jump Higher w Mike Murphy,” WaterSki Magazine, July, 1996, 53.

Some Rights Reserved. The TEXT ONLY of this publication MAY be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. All use MUST be accompanied with the attribution: “From Adventures in Water Skiing: Part 3, Hydrofoiling. Used with permission by http://tonyklarich.com”. TEXT ONLY is licensed under creative commons agreement (CC BY 3.0). The images (photos) MAY NOT be used, uploaded, reposted, or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission.